There was great jubilation in Gunnedah on August 15, 1945, as news came across the airwaves that the war was over – the celebration of the close of the War in the Pacific was a joyous day, with Pike’s Powerhouse whistle blowing continuously as the band led jubilant townspeople down Conadilly Street and continued playing all day.

The band for the Victory March comprised Rene Weakley, Vic Warner, Jim Schutz, Norm Dowling, Vic and Hector Reading, Merv Hughes, Fred Hunt, Walter Finlay, Harold Hazeltine, Len Pike, Tom Godbold and Arnold Morgan. Bill Board, then manager of the Commonwealth Bank, was the conductor.

The Town Hall was filled and Conadilly Street was jammed with revellers until the early hours of the morning.

Pat Studdy-Clift described the jubilation in her book Only Our Gloves On where she recalled life on the family property which during the war was issued Italian prisoners-of-war to help run the family property while the men were serving.

“We all gathered around the radio to hear the announcer repeating the news flash – the war had ended; we were at peace. Such utter relief and joy possessed us all, that we dropped whatever we were doing, changed into our Sunday best and went to town.

“Everyone, it seemed, had the same idea; people swarmed towards Gunnedah. In those days Gunnedah was a rather sober country town, lacking lustre, steeped in wartime gloom and stringencies, the paint had dulled on the buildings and the streets were empty and wide. But not on this day of victory. Suddenly the town was filled with people almost delirious with joy.

Where had all the people come from? Streamers and party toys had been dug out from bottom drawers. Musicians were installed on the backs of large trucks. Anyone who could play a musical instrument was recruited to provide music. The noise was indescribable.

Gunnedah was swept by a wave of celebration, a cacophony of sound – horns blowing, people singing and shouting, hugging and kissing. The normally undemonstrative Australian was letting down his guard. This was the greatest fun of all, an impromptu mass celebration of unrestrained joy.”

A civic service of thanksgiving, organised by the Ministers Fraternal, was held in Wolseley Park, to commemorate Victory in the Pacific and the conclusion of World War II, with God Save the King followed by hymns and prayers and an address by local minister Rev. RL McInnes who urged those present to always work for peace: “A new era is here. Let it be a better world, made up of better men and women. Let us do our part that true peace will come and last. Our children’s children are watching us to see if we can make the grade. While the sounds of guns and bombs die away, there is an inner war that continues. It is a war against the things that make war possible, it is a war to win true peace. We have entertained hopes and dreams for a better world. Shall that better world come; it is for us to decide by our living.”

As the excitement died down families began preparing for the return of their loved ones, while others grieved for those reported as missing in action or otherwise buried in a foreign grave.

Many returned with horrific injuries or were so mentally scarred that their lives would never be the same again.

Many died on the battlefields or as prisoners-of-war. Four soldiers from the Gunnedah district died on the infamous Sandakan death marches, in the closing stages of the war, including Pte Ted Le Cussan, Pte Jack Garrard, Gunner George Sefton, of Boggabri, Private NJ Bedford, of Curlewis.

Two POWs to survive and return home were the late Jim Sharpe and Alec Priest, with Jim Sharpe considering himself “one of the lucky ones” – lucky that he had not been sent to work on the Burma-Thailand Railway, to death camps in Borneo or the mines and docks in Japan. He recalled that those who went were, at the time, glad to get out of Changi but had no idea what lay ahead of them. He said the survivors who came back to Changi after the war ended were just skin and bone, hanging together by a thread, with ulcers to the bone on their arms and legs and barely able to walk.

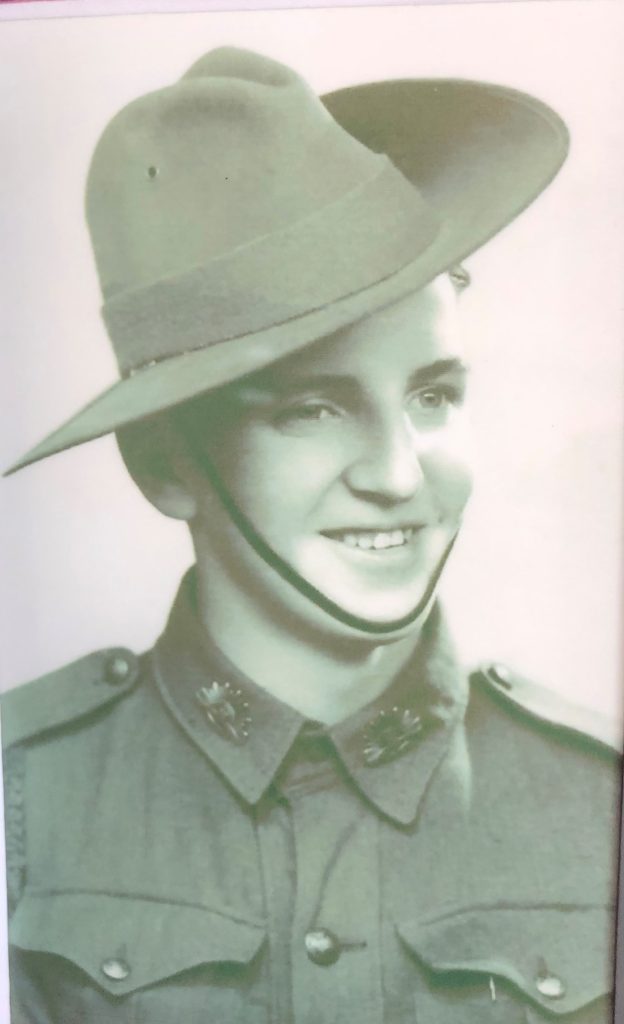

Jim Sharpe in his uniform during World War II.

A POW for three years and eight months, Jim Sharpe was caught up in the daily struggle to survive in Changi when Singapore was over-run by the Japanese.

Jim Sharpe was only 17 when he enlisted and was posted to the 10th Australian General Hospital unit as a nursing orderly. He was one of 133,000 Australian, British and Indian service personnel who were captured by the Japanese in the Fall of Singapore on February 15, 1942.

In an interview with the late Ron McLean in 1995, Jim recalled how the thousands of Australian prisoners were forced to sleep on concrete floors, with a groundsheet over them. As time wore on, food became scarce and disease swept through the camp.

From then until the end of the war, prisoners were subjected to unspeakable hardship – tortured, bashed, starved, made to work in appalling conditions, some even executed in front of their mates. He said conditions worsened when food and medical supplies started running low and there were bashings every day. After the war Jim went home to his parents in Ipswich but his love interest in the shape of his future wife Peggy drew him to Gunnedah. They had met in Manilla, while he was at camp in Tamworth in 1941. Mr Sharpe threw himself into the community after their marriage and he was especially prominent in rugby league circles becoming a life member of Gunnedah Rugby League Group 4, Northern Division and the Country Rugby League. He died in 2003.

Alex Priest was a walking skeleton when he returned to Australia after being captured in the fall of Singapore. Sergeant Priest, in charge of a Bren gun platoon of the 22nd Infantry Brigade, 1/18th Battalion, was among the 15,000 Australian men and women taken prisoner. He was interned in Changi prison camp and later sent to Blakamati Island, loading ships for convoy and working from dawn to dark. The prisoners were given only small quantities of rice and grain to eat and were regularly bashed by their guards.

During his internment, his wife Nan set up a beauty salon in Gunnedah and when her husband came home from the war, a shadow of his former self, he started his watch-making business in one of the hairdressing booths. The business expanded steadily over the years and became one of the most successful in the north. Mr Priest continued working until 1978 when his second son Charles came home to take over the running of the business.

Born in Glen Innes in 1913, Gunnedah was his adopted town of Alec Priest, who became a hard-working advocate for Gunnedah.

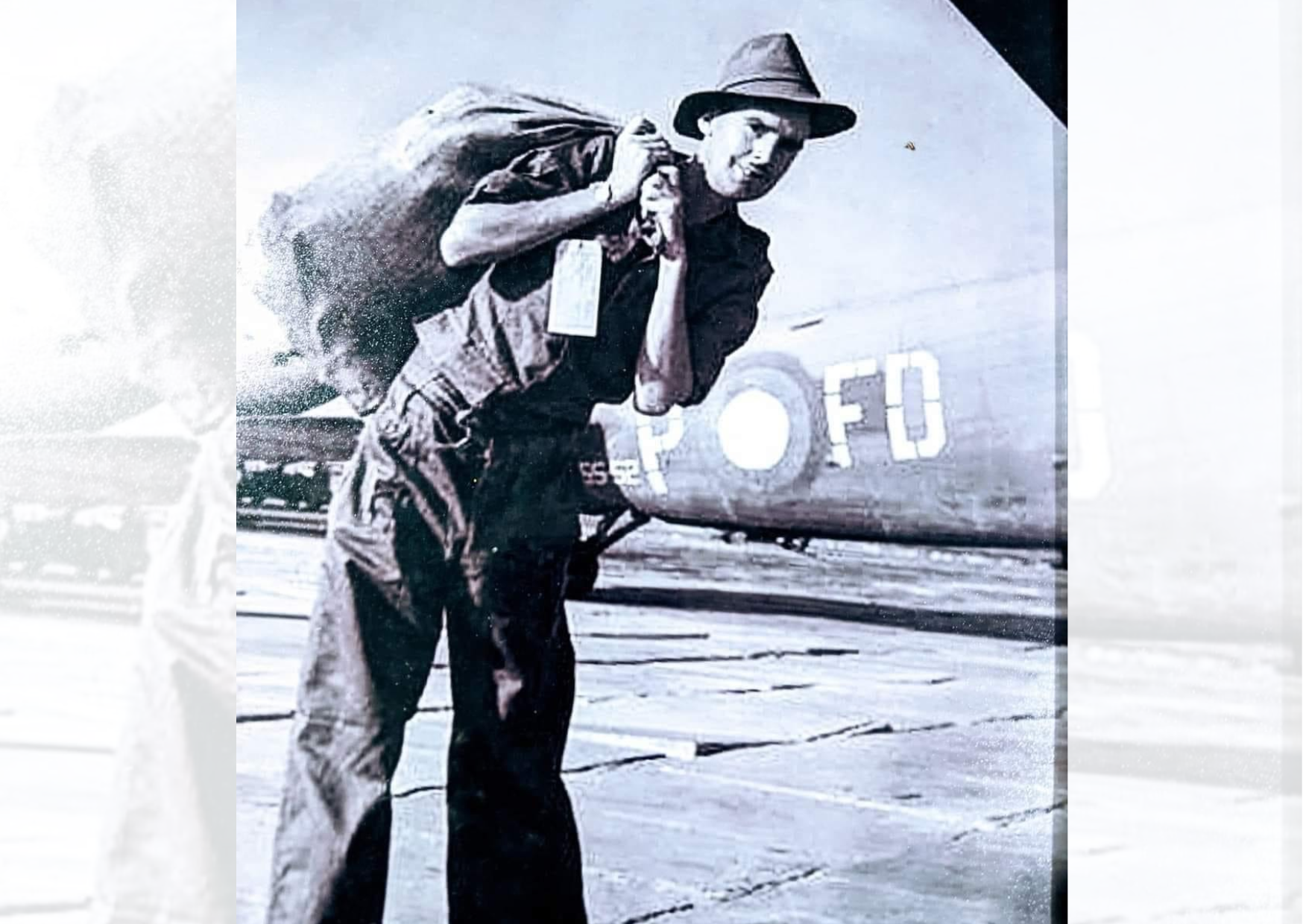

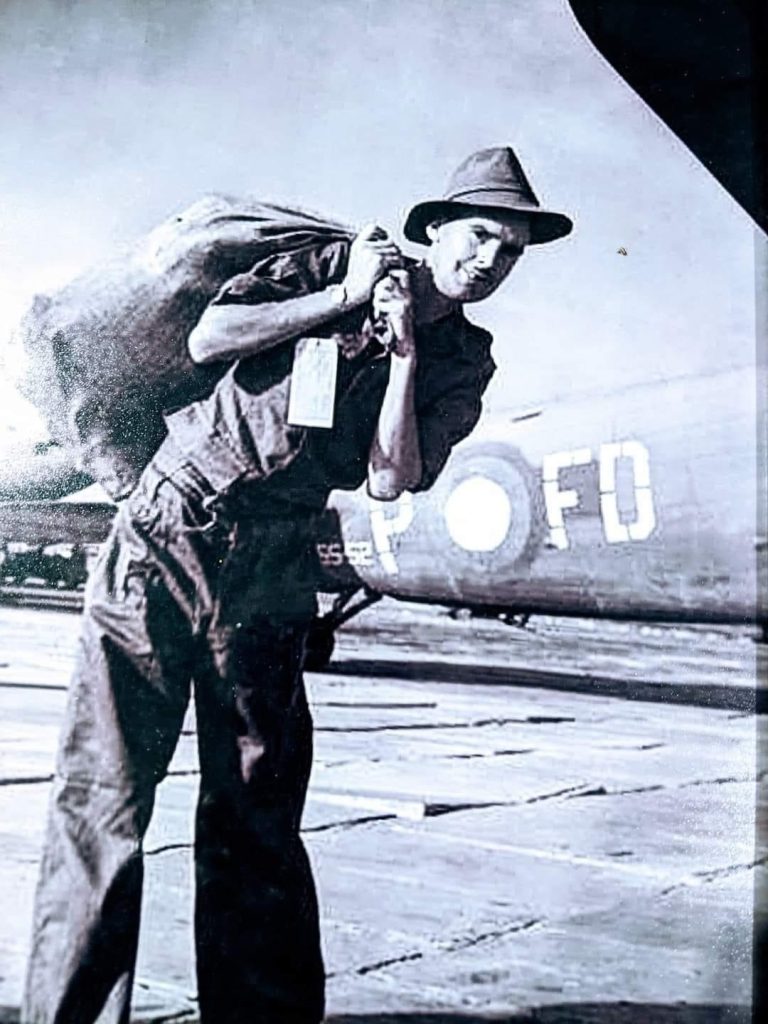

Sgt Alexander John Priest, 2nd 18th Battalion , 8th Division AIF. This Australian War Memorial image was taken upon his release from Changi Prison Camp.

Alec Priest threw himself into community work and in the 1950s was one of the main figures in the establishment of the War Memorial Pool on the site of a former rubbish dump in Anzac Park. He was one of the main fund-raisers for the scout and guiding complex in South Street and his wife Nan was president of that movement for many years.

He was president of the Servicemen’s Club from 1968 to 1972 and was associated with major extensions and improvements to the club premises over the years. Along with fellow POW, Tom Bowden, he was also one of the instigators of the avenue of trees in Eighth Division Memorial Avenue, dedicated to war service personnel who died in World War 2. After the avenue was officially opened, he unfurled the flag belonging to the 2/19th Battalion of the 8th Division which had been handed on to him for safekeeping after being hidden in Changi for the duration of the war. When the Japanese surrendered in 1945, the first act of the POWs was to unfurl the battalion flag. Every year since 1957 until his death, Alec Priest or a member of his family, raised the flag on Anzac Day on the memorial in the 8th Division.

A keen historian, he had a special interest in the expeditions of explorers John Oxley and Sir Thomas Mitchell in the 1800s. After the death of his wife in 1979, he sponsored the setting up of the Nan Priest Memorial in the Water Tower Museum, and the POW flag is held in trust at the museum. He died in March 1991, aged 77.

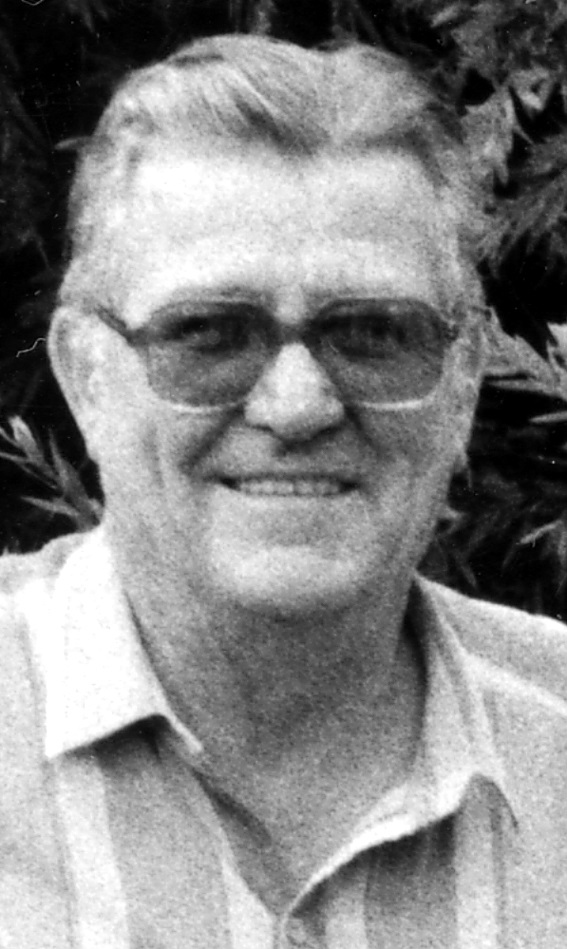

Another POW to survive was Tom Morris who had enlisted at the age of 17 and was captured in the fall of Singapore. He had been fighting as a corporal with the 22nd Brigade headquarters and was shipped to Burma where he was put to work on the infamous railway. Debilitated by Beri-Beri, malaria and dysentery, he was lucky to survive. He was then put to work in Thailand which was a hellhole for prisoners and hundreds died of disease, falls and brutal treatment by their captors. At the end of the war, he was repatriated and became a teacher, a career he held for 32 years. Later living in Canberra, he began acting for ex-servicemen in their negotiations with the Department of Veterans Affairs and volunteered at the Australian War Memorial.

Tom Morris had enlisted at the age of 17 and was captured in the fall of Singapore.

Around that time, he returned to Thailand with his wife Val and family and it was then that he conceived the idea of converting Konyu Cutting – which became known as Hellfire Pass – as a memorial to those who died on the railway. Other joined the project and it was a proud day for Tom Morris when then Prime Minister John Howard opened the memorial and museum and 4km of walking trail along the alignment of the railway. Tom Morris was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia OAM in 2000. He died in 2003 and the Hellfire Pass project lives on as a memorial to those who died but also soldiers like him who survived to tell the stories.

To order photos from this page click here