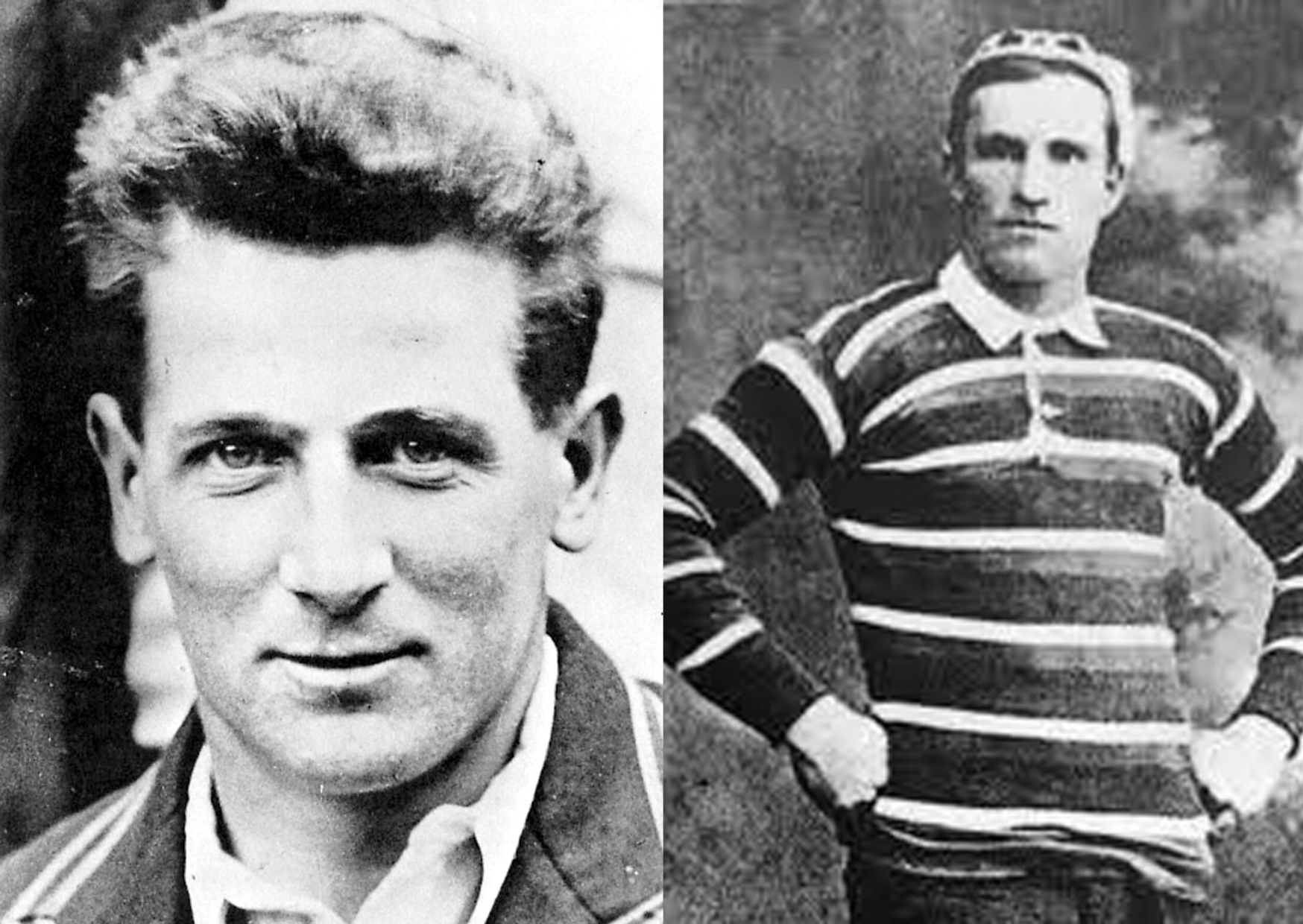

Gunnedah was once home to two of Australia’s most famous sportsmen who dominated the world of cricket and rugby league – Harold Larwood and Dally Messenger.

Harold Larwood was the scourge of Australian batsmen, the prime practitioner of Bodyline during the 1932-33 cricket series in Australia.

He was the stormtrooper in a plan hatched by England captain Doug Jardine to curb the phenomenal run-getting feats of Donald Bradman – by directing fast- pitched bowling at the body with a packed legside field waiting like vultures for a catch. So successful was the plan that England won the series 4-1 and Larwood claimed 33 wickets at an average of less than 20.

The Bodyline series is part of cricket’s history – though not written in gold, in view of the tension and bad feeling it created between the two countries.

Bodyline was universally condemned after the acrimonious series and Larwood became the scapegoat for it, even though Jardine was the architect and he (Larwood) merely the loyal servant. Larwood fell out with the English cricket establishment after the Australian tour and, in fact, never played another Test, retiring from the game a bitter and disillusioned man.

Yet, ironically, despite the acrimony of the 1932-33 tour, Larwood and his family eventually migrated to Australia – and their first home was in Gunnedah.

The long trail for the Larwoods led from Blackpool, where they had a small mixed store, to the fuel agency of Gunnedah identity and long-serving mayor and MP, the late Frank O’Keefe. The architect of Larwood’s migration was former Australian opener Jack Fingleton, one of those who had taken a battering from Larwood in 1932-33.

In his book, Brightly Fades The Don, Fingleton described how he and former English wicket-keeper George Duckworth had gone to see Larwood in his Blackpool shop in 1948.

“He recognised me immediately, though I was the first Australian cricketer he had met since those stormy days of 1932-33,” Fingleton wrote.

Cricket had lost all its appeal to Larwood and he was still bitter over his treatment. He had not seen the 1934 and 1938 Australian sides in England and couldn’t remember the last time he had been to Trent Bridge, scene of so many of his triumphs.

But he expressed a wish to emigrate to Australia, believing there would be more opportunities there for his daughters. And that was how he ended up in Gunnedah.

Jack Fingleton was a friend of Frank O’Keefe, who was then a NSW Cricket Association official. When Fingleton mentioned that Larwood was interested in living in Australia, Frank O’Keefe told him he could give him a job and lodgings until he found his feet.

So, Harold Larwood, famous English cricketer, his wife Lois and their five daughters came to Gunnedah in 1950. They stayed with Frank and Nan O’Keefe and Larwood worked in the fuel agency.

By all accounts, the family was happy in Gunnedah but they eventually decided to move to Sydney, because there would be more opportunities for the girls. In Sydney, the family lived at the one address, 7 Leonard Street, Kingsford. Harold Larwood died after a short illness in July 1995, aged 90.

Herbert ‘Dally’ Messenger, first superstar of rugby league in Australia died in Gunnedah on November 24, 1959 – despite his star-studded career in rugby league he fell on hard times later in life and for many years lived in hotel rooms and at the NSW Leagues Club. He was befriended in the 1950s by Gunnedah publican Con Barbato, who invited him to stay at the Court House Hotel. He came to Gunnedah in early 1959 and lived quietly at the hotel until his death.

Born at Balmain, on April 12, 1883, he was the son of Charles Messenger a boatbuilder from Middlesex, England, and his Melbourne-born wife Anne Atkinson.

Nick-named Dally and sometimes The Master, Messenger was a leg-end in his playing career, firstly in rugby union and then in the breakaway code, rugby league, when it was formed in 1907-08.

When the founders of rugby league sought to establish their code in 1907, they realised that luring Dally Messenger, the star of rugby union, was their best chance of winning public acceptance. At the same time, the breakaway code was launched in New Zealand, and a team of “paid” players was selected to tour England, where the Northern Union had been established in 1895.

The Sydney officials invited the New Zealanders to play three matches in Sydney on the way, hoping to “woo” Messenger to league before their arrival. When the officials went to Messenger and offered him 50 pounds a match, his reply was “see what Mum says”.

Mum said “yes” and Messenger joined the rebel code. The three games were a huge success, producing a profit of 180 pounds which went into a fund for further development of the game.

The New Zealanders were so impressed with Messenger’s extraordinary flair that they asked him to join them on their tour of England. He did – and he was a sensation on tour. In one match in England, he retrieved a ball behind his own goal-line, dummied, changed course and beat the whole team to score a try.

Just as spectacular was his kicking – in a match at Hunslet in England, he kicked a goal from just outside his own 25-yard line. On another occasion, during an exhibition, he kicked 11 out of 12 goals from the sideline into the teeth of a gale.

Messenger came home with 200 pounds and an outfit of clothes, the most he ever made from league. The following year he went back to England with the first Kangaroos, again dazzling the crowds. In the 1910 home series against England, the visitors described him as the greatest footballer they had seen in any code.

Messenger captained Australia, NSW and his club, Eastern Suburbs, which won the 1911, 1912 and 1913 premierships.

He married Annie Carroll in 1912 and together they ran a hotel in the city. His business and family interests led to his retirement from league in 1913. Later he had a banana plantation in Queensland, which was a failure. The couple then bought the Royal Hotel in Manilla but his wife caught pneumonic influenza and died soon after their arrival.

Dally Messenger became sick in October 1959 and spent a week in Gunnedah hospital. He was discharged but again became ill and was re-admitted. He died on November 24, 1959, at the age of 76.

In July 1950, the touring English rugby league team came to Gunnedah to play Northern Division on a water-logged Kitchener Park.

A newspaper report of the day, described the match as “a splendid exhibition of open football, in which team work predominated, the English side defeating the Norther NSW side 41-4, in challenging conditions”.

The article reported that the Englishmen’s display was more remarkable because of “the nature of the ground”.

Before the game had been in progress many minutes the players were covered in mud.

Pools of water were everywhere along the side of the field and the ball became increasingly difficult to handle as the match progressed; The Englishmen ran up a lead of 18-4 at half-time even though early in the second session, first Featherstone and then Hilton left the field – Featherstone with a rib injury and then Hilton with an injury to the ankle. The article continued reporting that “the English side gave the crowd of nearly 5000, a brilliant exhibition of football even though the ground was a quagmire”.

To order photos from this page click here