Irving Thompson, of Gunnedah, was only a boy when he was killed in battle, trying to rescue wounded soldiers from no-man’s-land.

He and his older brother, Victor Wright Thompson, joined up in 1915, following a rallying speech by the leader of the Australian Opposition, Joseph Cook, who made an impassioned call for enlistments to help the Empire “punish … those maiming, murdering and poisoning Huns”. The boys were the sons of Wright and Hannah Thompson, who owned the property Rockvale, which much later became the site of the Gunnedah Abattoir.

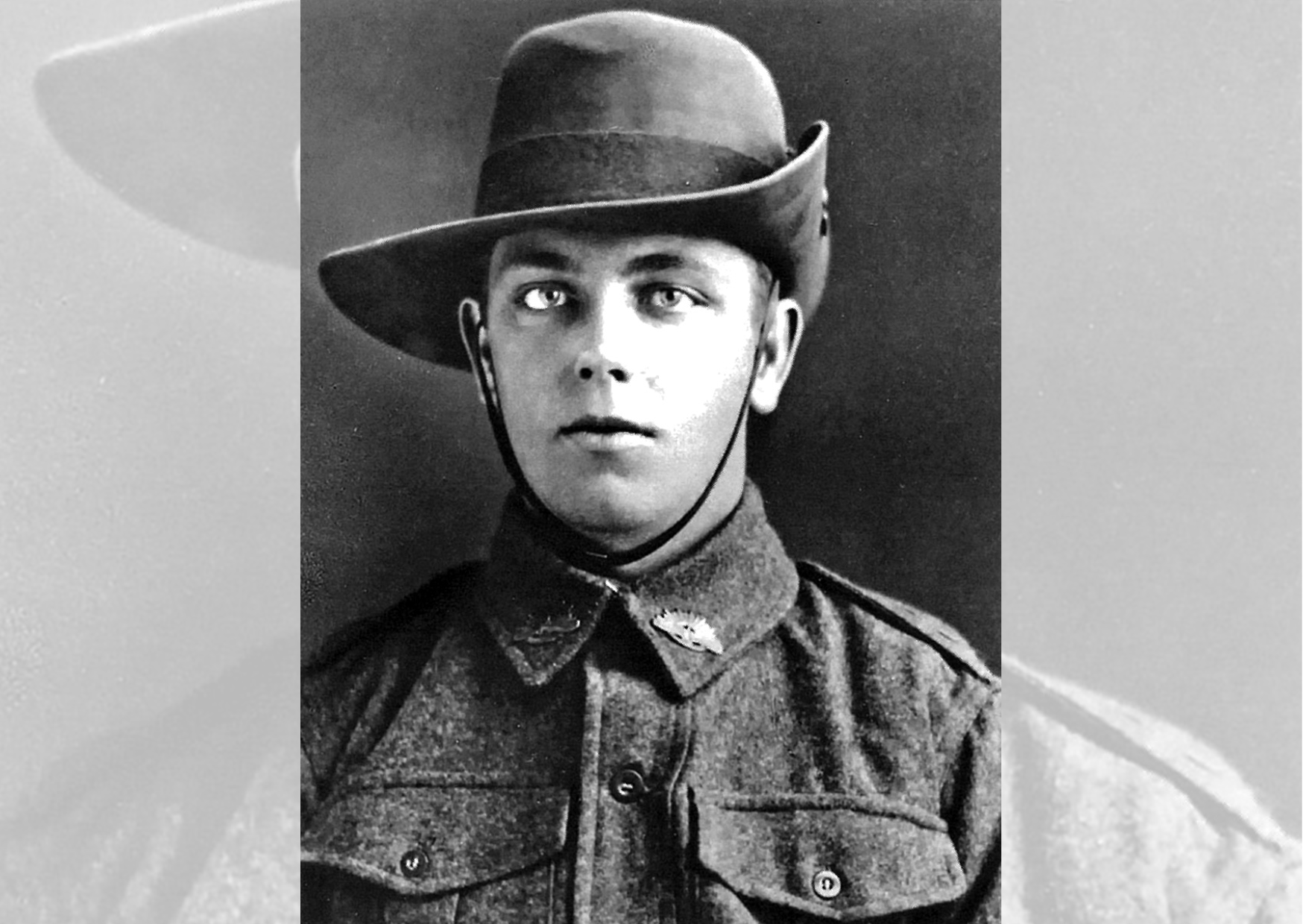

Irving Thompson, the Gunnedah boy who died at Fromelles, trying to rescue wounded soldiers from the battlefield.

Victor and Irving were among the thousands to enlist in the wake of Joseph Cook’s rallying call. Irving enlisted on August 8, 1915. His enlistment papers place his age at the time as 18 years and nine months. It was later found that he had increased his age to sign up. Attached to the 6th Re-inforcements, 17th Battalion, in October 1915, he was later transferred to the 55th Infantry and then to the 5th Pioneer Division. His trade was described as ironmongery.

With reinforcements desperately needed for the front, the Thompson brothers sailed in a convoy of ships that arrived in Egypt on December 5, 1915, the day their youngest sister Nea was born.

They made the journey in separate ships and in different units but, on arrival in England, they were despatched almost immediately to northern France.

Irving Thompson was pitched into battle at Fromelles, an engagement which exacted the highest toll on Australian forces for the whole of the war – in one night (July 19-20, 1916), 5533 Australians became casualties, among them 1933 dead. British generals were accused of ineptitude and poor planning in sending out inadequately-prepared infantry on a too-narrow front and against heavy enemy artillery. Troops had to advance 400 metres across open country in the face of murderous machine gun fire.

Irving Thompson was one of the 20 per cent of Australian forces who escaped death or wounding that night.

His unit was engaged in digging communication trenches in shocking conditions under continuous fire and grenade attacks.

Renowned war correspondent C.E.W. (Charles) Bean reported that “the wounded could be seen everywhere, raising their limbs in pain or turning helplessly hour after hour from one side to another. The scene in the Australian trenches packed with wounded and dying was unexampled in the history of the A.I.F.”.

The following day, Irving volunteered to try to rescue wounded and dying soldiers, still lying in no-man’s-land. But he, too, became a statistic, cut down by machine-gun fire.

Later in the day, Major A.V. Murdock, of the Victorian-raised 29th Battalion, produced a makeshift Red Cross flag and walked towards the German lines, handing out water bottles to stranded soldiers. Offering himself as a hostage, he made a deal with the enemy for a brief truce to allow the wounded to be collected.

The deal went ahead and around 300 were rescued, though by then it was too late for Irving Thompson. He was buried in Rue-de-Bois Military Cemetery near Armentieres.

Victor Wright Thompson won the Military Medal for his actions in enemy engagements on the Hindenburg Line near Bullecourt in May 1917. He was also awarded the French Croix de Guerre and was twice mentioned in despatches.

This was featured in In the Line of Fire, by acclaimed Gunnedah historian the late Ron McLean. Mr McLean was a long-time editor of the Namoi Valley Independent and later helped to establish the Gunnedah Times.

To order photos from this page click here